The Notecard System

The Notecard System: Capture, Organize, and Use Everything You Read, Watch, and Listen To - Billy Oppenheimer

Excerpt

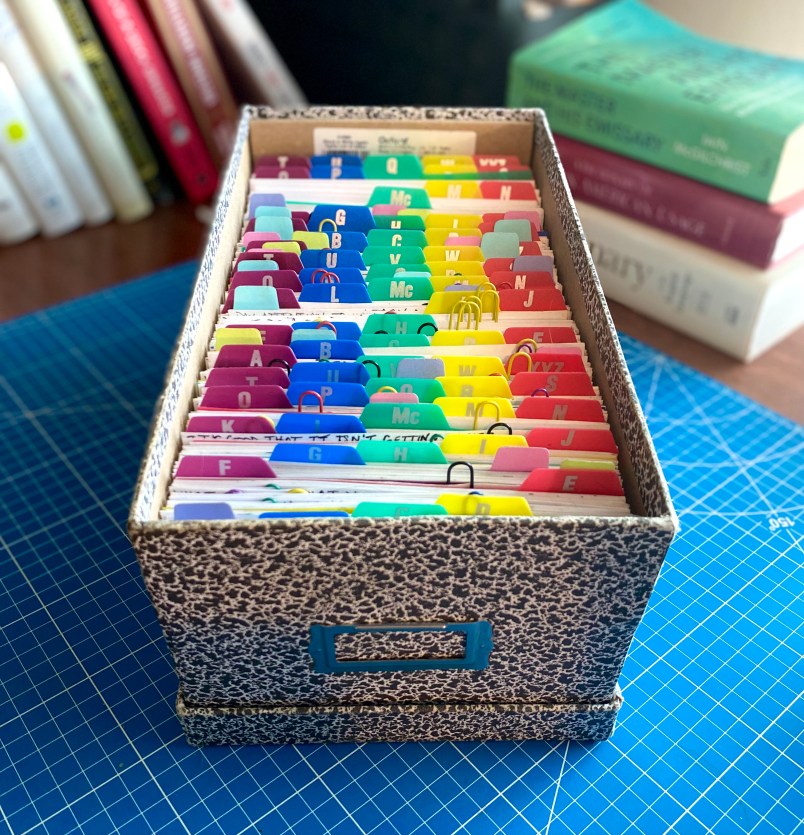

Below, I am going to explain my adapted version of the notecard system. The structure, like the system, is not sequential, so click the links and jump around if you wish. And there are a lot of pictures and examples throughout, so don’t let the scroll bar deceive you—it’s not that long. I. Who Needs […]

Below, I am going to explain my adapted version of the notecard system. The structure, like the system, is not sequential, so click the links and jump around if you wish. And there are a lot of pictures and examples throughout, so don’t let the scroll bar deceive you—it’s not that long.

- Who Needs The Notecard System? — my answer to, who should implement the notecard system? Who shouldn’t?

- Note-taking Principles — the 5 core principles underlying my note-taking process.

- The Notecard System — how I capture stories, ideas, and research I come across when I read books and articles, listen to podcasts, and watch documentaries and YouTube videos.

- Frequently Asked Questions — answers to the questions I frequently get asked.

- Other People Who You Use The Notecard System — resources to read about and learn from other people who use the notecard system.

- Conclusion — a closing argument for The Notecard System and what you get out of it.

I. Who Needs The Notecard System?

“The greatest genius will never be worth much if he pretends to draw exclusively from his own resources.” — Goethe

In Game 1 of the 2018 Eastern Conference NBA finals, the Cleveland Cavaliers lost to the Boston Celtics 108-83. After the game, Cavaliers’ star Lebron James was asked about a stretch where the Celtics scored seven straight points. What happened there? the reported asked

What happened? James repeated back to the reporter. He pauses, seems like he might dismiss the banal question, then perfectly recalls, “The first possession, we ran them down all the way to 2 [seconds] on the shot clock. [The Celtics’] Marcus Morris missed a jump shot. He followed it up, they got a dunk. We came back down, we ran a set for Jordan Clarkson. He came off and missed it. They rebounded it. We came back on the defensive end, and we got a stop. They took it out on the sideline. Jason Tatum took the ball out, threw it to Marcus Smart in the short corner, he made a three. We come down, miss another shot. And then Tatum came down and went ninety-four feet, did a Eurostep and made a right-hand layup. [We called a] timeout.” The other reporters in the room laugh. “There you go,” James says.

“People always say of great athletes that they have a sixth sense,” Malcolm Gladwell says in Miracle and Wonder: Conversations with Paul Simon.

“But it’s not a sixth sense. It’s memory.” Gladwell then analogizes James’ exacting memory to Simon’s. In the way James has precise recall of basketball game situations, Simon has it of sounds and songs. “Simon’s memory is prodigious,” Gladwell says. “There were thousands of songs in his head. And thousands more bits of songs—components—which appeared to have been broken down and stacked like cordwood in his imagination.”

The archive of situations James has in his memory function as reference points to decipher new but analogous game situations, to enable intelligent decisions, to facilitate anticipation.

For Simon, those reference points facilitate his creative output. He cultivates an archive of sounds he likes that become the building blocks for his own songs. As Gladwell says, for Simon, “songwriting is the rearrangement and reconstruction of those pleasurable sounds.”

Simon’s musicianship is a function of the library of musical components in his head. Everything he creates is largely an amalgamation of bits from his musical memories. Simon recognizes this to be his gift: “I seem to have a very exact memory of things that I’ve heard—liked and disliked—but very exact,” he says.

If you are like Lebron James or Paul Simon, if you were born with a gift for recall, you might not need a note-taking system.

But if you are like the rest of us, you should have a notetaking system. You should capture the things you might want to later recall. You should cultivate an external memory bank, a library of components you can rearrange and reconstruct to your liking and needing.

Whether you write screenplays or emails, design sneakers or powerpoints, arrange music or spreadsheets—you create things. You use your brain to bring things into existence. To bring things into existence, your brain rearranges and reconstructs the material available to it.

And improving the quality and quantity of material available to your brain when you sit down to create something—that is why we implement The Notecard System.

II. Note-taking Principles

A lot of people ask Ryan how he produces so much output.

My dad has a custom apparel business, and I worked in the factory growing up. While he produces some 60,000 items of decorated apparel each year, no one asks him how he does it. How he does it isa warehouse of garments and fabrics and spools of thread and rolls of cad-cut film and thermo film that get pulled and pieced together by skilled embroidery and press operators and then cleaned and trimmed and ironed and inspected and folded and boxed then shipped.

Ryan’s production is a function of a similar process.

He has a warehouse of notecards with ideas and stories and quotes and facts and bits of research, which get pulled and pieced together then proofread and revised and trimmed and inspected and packaged and then shipped. If you develop a process and commit to that process, Ryan says, books come out the other side. They aren’t feats of genius or works of magic or flashes of inspiration. They’re products of process. They’re products of The Notecard System.

Which brings me to the first principle of my notecard system:

Do Not Copy and Paste

Mitch Hedberg joked that he kept his pen and paper on the other side of the room. Then when he had an idea for a joke—if he couldn’t convince himself to get up and go get the pen and paper, the joke must not be good enough.

If you can’t talk yourself into using your energy to write or type something out, it’s probably not worth capturing.

The novelist and screenwriter Raymond Chandler said he avoided reading books written by someone who didn’t “take the pains” to write out the words. (It used to be common for writers to dictate into a recorder then have an assistant transcribe those words.)

“You have to have that mechanical resistance,” Chandler wrote in a 1949 letter to actor/writer Alex Barris. “When you have to use your energy to put those words down, you are more apt to make them count.”

When you don’t have that mechanical resistance, when you give yourself the freedom to copy and paste, you’re not discerning. You capture anything and everything that strikes you at first glance. It’d be like if you stored everything you underline in a book you read. Anyone who has gone back through what they underlined in a book they read knows you don’t want to capture everything you underline.

When I get an email from someone who has taken thousands of notes but can’t seem to put them to use, I ask if they are copy-and-pasters. They almost always are. So their Evernote or Roam or Notion database is unwieldy. There may be some quality insights in there, but they’re lost among all the crap they copy and pasted.

Be discerning. Take the pains to write things out.

Use Time As A Filter

When I finish a book, I put it back on the shelf for a week or two. After a week or two, when I have a block of time, I grab the book and a stack of 4×6 notecards.

The reason to wait a week or two? Time is a great filter. Even with a really good book—one where I fold over every other page—I might only make 5-10 notecards. With the passage of some time, you find most things that you underline don’t hold up.

The interesting information, you realize, actually isn’t that interesting. The great anecdote, you realize, actually isn’t worth the cognitive energy required to write it out in your own words. So, I move from one folded page to the next, asking myself, is this worth the energy? When the answer is yes, I try to make a notecard as if I might want to later transfer it directly into a piece of writing.

(Quick aside: I hear from people who somehow have their Kindle app and their note-taking app synced up so that everything they underline goes straight into their note-taking app. I think this is a terrible thing to do.)

Take Notes For A Stranger

One of the big lies notetakers tell themselves is, “I will remember why I liked this quote/story/fact/etc.”

The German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, who was famous for his “slip box” or “zettelkästen” method, called his box of notecards his conversation partner. He made each note card as if someone else were going to read it. Because, he would point out, by the time he came to a card a couple days/weeks/months later, he would be someone else. You may have had the experience where you flip through a book you read and marked up some time ago, and you have no idea what you were liking about something you underlined or what you meant by this or that comment in the margin.

So I make every note card with the assumption that I will later have forgotten just about everything about the book/article/paper/interview from which the note card comes from.

If I am capturing an interesting idea, for instance, I surround it with context—the way it might appear in a paragraph in an article. (much more on this and many examples below).

The note card should be able to communicate a complete thought or idea or story or lesson that an ignorant audience (me) can understand, learn from, or be surprised by.

“One of the most basic presuppositions of communication,” Luhmann writes, “is that the partners can mutually surprise each other.” Which is one of the joys of the notecard system—when you surprise yourself, when you rediscover, when you find the perfect card while you were looking for something else.

Let The Notes Determine The Themes

One of the big breakthroughs for me with this system was to let the notes/categories determine the categories/themes/sections, not the other way around.

So originally I thought, I need a bunch of categories and themes first then I’ll keep my eyes and ears out for things that fit into those topics and themes. What I found was that if something caught my attention but I didn’t have a topic/theme to slide it into, I didn’t write it down.

Now my thinking is, i_t caught your attention for a reason – capture it and figure out where it belongs later._

So I’ve got a section in the front of my box of notecards that is the “Waiting Room.” What happens is, over time, I’ll draw a connection between three or four cards and then move those to their own section with a card up front with a kind of index (more on this below).

Regularly Review The Collection

In Getting Things Done, David Allen talks about how when you write something down, you are essentially telling your mind, ‘mind, you don’t have to remember or remind me about this.’ This is very helpful in the context of task management: if you are trying to focus on Task A but Task B is lingering in the cognitive background, if you write down when/where/how you will complete Task B, Task B tends to disappear from the cognitive background (in other words, your mind stops trying to remind you of Task B because it trusts it doesn’t have to).

In the context of knowledge management, this is less helpful. In the context of the notecard system, you write something on a notecard because you want to remember it. But when you write something on a notecard, I have found, you are essentially saying, ‘mind, you don’t have to remember this.’

If the “Take Notes For A Stranger” principal above is a branch on a tree that represents an assumption that I don’t have as good a memory as I think I do, this principal is a stick that stems off of that branch.

At least once a week, I sift through all my notecards before I write my Sunday newsletter. And every time, I find cards I have no recollection of making. So I’ve come to agree with the following.

Randall Stutman, an executive advisor and prolific note-taker, says, “collecting insights is just the preamble to what really matters: reviewing, with some level of consistency, those insights. You have to routinely make those insights available to yourself.”

“Wisdom is only wisdom if you can act on it,” Randall says. “In the review process, you’re making those insights available for your mind to act on.”

Physical or digital, I think whatever system gets you to look forward to consistently reviewing what you’ve collected (read: forgotten) is the best system.

“For every good idea that comes out of you, you need ten good ideas coming into you. And that’s up to you to ensure that you continuously fill yourself up with fresh knowledge and information and impressions so that one thing can come out.” — René Redzepi

Like any system, the notecard system needs inputs.

Whether you use physical notecards or an app like Evernote, Obsidian, or Notion—your collection of notes is a function of the content you consume.

A rough estimate, but 75% of my notecards come from books, 13% from podcasts, 10% from articles, and 2% from videos (YouTube, documentaries, movies, etc.).

My consumption strategies vary slightly across mediums, but they all stem from what I learned from one of my reading heroes, Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Emerson liked to identify four classes of readers: the hourglass, the sponge, the jelly-bag, and the Golconda. The hourglass takes nothing in. The sponge holds on to nothing but a little dirt and sediment. The jelly-bag doesn’t recognize good stuff, but holds on to worthless stuff. And the Golconda (a rich mine) keeps only the pure gems. “Emerson was the Golconda reader par excellence,” one biographer writes in a little book on the role of reading in Emerson’s creative process, “or what miners call a ‘high-grader’—a person who goes through a mine and pockets only the richest lumps of ore.”

Of his huge book collection, it was said that Emerson had a bigger appetite than intake. He glanced at thousands of books, only reading carefully when his attention was fully captured. He believed it was the book’s job to fully capture his attention. So he had no problem moving on from a book after the first page, the first chapter, the first half—whenever he caught his attention fading.

He was on a relentless hunt for that feeling when a book really has you hooked in its teeth. You know it if you know it. “Learn to divine books,” Emerson once advised a friend, “to feel those that you want without wasting much time. Remember you must know only the excellent of all that has been presented. But often a chapter is enough. The glance reveals what the gaze obscures…You only read to start your own team.”

You only consume what others created to do your own creating. “There is then creative reading as well as creative writing,” Emerson said. “The discerning will read…only the authentic utterances of the oracle—all the rest he rejects.”

With that said…

- What I choose to read:

- wide funnel, tight filter—start a lot of books/articles and quit most of them. If I catch myself trying to convince myself to stay with a book/article, I stop reading it. There’s a certain feeling when a book captures your full attention…I’m searching for that.

- chain smoking—light the start of the next book with the end of the previous book: if I really like a book, my next book is one that was either mentioned in the book or in the book’s bibliography.

- trust but verify—start every book/article referenced or recommended by someone with good taste. But again, if it doesn’t capture and hold my attention, I’m quick to move on.

- What I choose to listen to:

- all of the above, and:

- people not podcasts—I don’t have any go-to podcasts. I get interested in someone—a writer, a musician, a comedian, a chef, an entrepreneur, etc.—then I search what podcasts they’ve been on.

- What I choose to watch:

- all the above, but less frequently.

The way I bookmark things I might ultimately transfer onto a notecard also varies slightly across mediums.

I will show you those various methods, starting with books…

Books

I mostly read physical books. I have an iPad with the kindle app, which I use only in the following way. If someone recommends a book or if I see a book referenced in another book or if I’m listening to a podcast and a book gets mentioned or etc., I will download the kindle sample. I will read that sample (usually the first 10% or so of the book) on the iPad and if i get hooked, I order a physical copy.

I like to read with a pen. (This is my favorite pen because it writes like a sharpie but doesn’t bleed through the page of a book or a notecard).

When I come across interesting information, I underline then write a corresponding question in the margin. So what I underlined is an answer to the question.

For example:

This, I find, is helpful when you go back through the book. The question in the margin sparks a recollection of the corresponding information. And typically, it does so faster than it’d take to reread that information.

When I come across an anecdote I like, I write a corresponding phrase in all caps in the margin. So I ask myself, “if this were to appear in a future article or newsletter or etc, what might the title or header be?”

For example, I recently read about how Lin-Manuel Miranda tells the same story dozens of times to the same person because he forgets who he already told. Once, when he finished telling his collaborator Tommy Kail a story, Kail said, “That happened to me. I told you that.” They both laughed then Kail added, “That’s why you’re cut out for theater, because you’ll tell it like it’s the first time.” So in the margin I wrote, LIKE IT’S THE FIRST TIME:

I’ll draw those squares around names, book titles, a good phrase, anything I might want to catch my eye when I am going back through the book.

When I come across something that reminds me of some other story or idea or etc., I write “<=> INSERT RELATED THING” in the margin.

For example, I recently read this idea of matching your selling techniques to people’s buying habits. That reminded me of something I once heard Nick Thompson talk about. He was asked what he learned from playing the guitar on NYC subway platforms. He said he learned that you gotta figure out who your ideal demographic is and then you gotta go to the subway platform they are most likely going to be at. You gotta meet your people where they are:

And then, as I mentioned with the “Let The Notes Determine The Themes” principle above, when I draw a connection between three or four cards, those become a section with a card up front with a kind of index.

For example, here’s a collection of cards from a section around simplicity/reducing things down to the atomic unit:

(And here, you can see how some of those cards become a newsletter issue).

If a notecard could fit in multiple sections, I do this:

So that’s basically what I’m doing when I read: I’m looking for interesting information, I’m on the hunt for stories, and I’m trying to make connections. Oh, and whenever I underline or write in the margins, I fold over the page. If it’s the left-hand page, I fold the bottom corner. If it’s the right-hand page, I fold the top corner. That way, if I want to fold both sides of the same page, I can.

When I finish a book, I put it back on the shelf for a week or two. After a week or two, when I have a block of time, I grab the book and a stack of 4×6 notecards. The reason to wait a week or two? Time is a great filter/editor. Even with a really good book—one where I fold over every other page—I might only make 5-10 notecards.

As I talk about above with the “Do Not Copy and Paste” core principle, with the passage of some time, most things you underline don’t hold up. (Quick aside: I hear from people who somehow have their Kindle app and their note-taking app synced up so that everything they underline goes straight into their note-taking app. I think this is a terrible thing to do.) The interesting information, you realize, actually isn’t that interesting. The great anecdote, you realize, actually isn’t worth the cognitive energy required to write it out in your own words. So, I move from one folded page to the next, asking myself, is this worth the energy? When the answer is yes, I try to make a notecard as if I might want to later transfer it directly into a piece of writing.

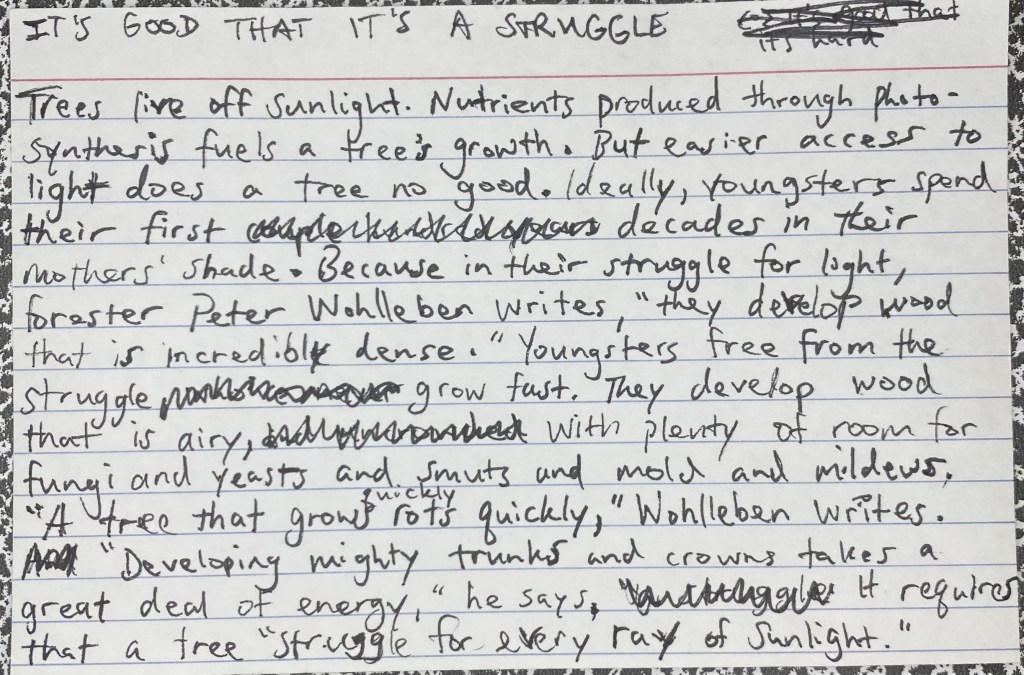

For example, in the book The Secret Wisdom of Nature, I liked the idea that trees that have to struggle for sunlight grow stronger and live longer than trees that are free from that struggle:

A month or two after reading this, I made a notecard…

(I put a title of some kind at the top of every card. This is helpful when I finger-tip through the cards—in a glance, I can tell if it’s what I’m looking for).

A few weeks after making the notecard, I wrote about how the actor Jeff Daniels decides what jobs to take on. Basically, he only takes a job if it will be challenging. His explanation reminded me of the idea that trees that have to struggle get stronger:

On the back of the notecard, I put the book title and page number(s).

Next up…

Podcasts

There must be better ways to do this, but this is what works for me.

I typically listen to podcasts when I am on the move: running, walking, driving, etc. So when I’m listening to a podcast, as soon as I hear something I might want to later transfer onto a notecard, I copy the link into a note in Notion titled “Podcasts” then put the name of the person getting interviewed.

Then, like I do in the margin of books, next to a time stamp, I put either a question or a phrase that corresponds to what the person said.

For example, I recently listened to a podcast where David Sacks talked about how, when he’s stuck on problem, he assembles smart people he trusts, and tries to get a variety of advice/opinions out on the table. He analogized it to taking the Rubik’s cube out his head, putting it on the table, letting others have it for a while, then putting the cube back in his own head. So I made this note:

If I am reminded of some other idea, I write “<=> INSERT RELATED THING” below the question.

For example, I listened to a podcast where Marc Andreessen advised against starting what he called “synthetic startups,” which he said is when you start with just wanting to be an entrepreneur and try to work backwards to an idea. It can work, he said, but in his experience, it’s rare that a synthetic startup works. Successful startups, Andreessen said, more commonly happen as follows. You have been immersed in an industry for five to ten years. You work tediously and tirelessly to develop to earn the ability to know the industry inside-out. With the eye of expertise, you see that something should work a different way. “If it’s an organic idea that comes out of something you’ve been deeply immersed in,” Andreessen said, “then you might be onto something.”

This reminded me of Robert Greene’s definition of creativity, which is that creativity is a function of putting in lots of tedious work. “If you put a lot of hours into thinking and researching and reading,” Robert says, “hour after hour—a very tedious process—creativity will come to you.”

So I made this note:

As I said with my reading process, I’m a believer in letting time be a kind of editor. So every so often, I scroll through this note and see what ideas or stories or etc. still excite me. When something jumps out, the notecard process here is the same: I write a title/header at the top of the notecard then try to make the contents of the notecard as if I might want to later transfer it directly into a piece of writing.

For example, on a few different podcasts, I heard Kobe Bryant talk about how he was terrible at basketball when he first started playing then taking an iterative approach to getting better and better.

A few weeks later, I made a notecard:

Which later made it into a piece about a race to the South Pole and ice ages:

On the back of the notecard, I put the title of the podcast and a timestamp.

Next up…

Articles

The only thing new to report here are some tools.

I typically come across an article I might want to read when I don’t have time to read it right then and there. I’m checking email and some newsletter links to some article. Or I’m scrolling twitter and someone shares something. Or I’m researching something for work and stumble on an irrelevant but potentially interesting article.

In these cases and others, I copy and paste the link into the read-later app Instapaper. It syncs across phone, iPad, and computer, but I typically read articles on my iPad before bed.

My article reading process is an adapted version of my book reading process.

When I come across interesting information, I highlight then comment a corresponding question:

When I come across an anecdote I like, I highlight then comment a corresponding phrase in all caps:

When I come across something that reminds me of some other story or idea or etc., I comment “<=> INSERT RELATED THING” like this:

Again, time is the best filter. I never immediately read an article then make a notecard. Like with the podcast process, every so often, when I’ve got a block of time, I open Instapaper and look at what I’ve read and the notes I took. When something still excites me, the notecard process here is the same: I write a title/header at the top of the notecard then try to make the contents of the notecard as if I might want to later transfer it directly into a piece of writing.

For example, a few weeks after I came across this short article by biographer Andrew Roberts about Napoleon’s “extraordinary capacity for compartmentalizing his mind,” I made a notecard:

Which later made it into a piece about Attention Residue:

On the back of the notecard, I put the title of the article and the author.

Next up…

Videos

Because stuff from videos, as I said above, only makes up ~2% of what I ultimately transfer onto notecards, I will just say the following.

This process is identical to the podcast process.

I have a note in Notion titled “Vids,” where I either add a link (if it’s a YouTube video) or a title (if it’s a movie or documentary) then a timestamp before a question, phrase, or connect.

So those are the processes and tools I use for various mediums.

Now, the questions I’m frequently asked about my notecard system…

IV. Frequently Asked Questions

Do you use the same box as Ryan?

No. Ryan uses this one. I use this one. Both hold 4×6 notecards (I just use these basic notecards. Ryan gets 4×6 notecards custom made for whatever project he is working on—for example). I went with a smaller box because it appears to fill up faster and that is satisfying. Also, it—along with my laptop, iPad, some pens, and a few books—fits in this Carhartt bag I take wherever I go.

How has your system evolved over time?

As I said in the “Let The Notes Determine The Themes” section, the biggest change for me has been from thinking about how a card fits into a theme to indiscriminately capturing things that interest me enough that I will take the pains to write it down.

How do you make sure you don’t lose track of cards?

I don’t make sure I don’t lose track of cards. As I said above and as some of the people below talk about, one of the joys of the system is when you surprise yourself, when you rediscover, when you find the perfect card while you were looking for something else.

What time of day do you typically make notecards?

Usually in the afternoon after I’ve completed work-related writing/tasks.

Do you do all your writing longhand?

No. Aside from notecards, I do all my writing in custom template I made in Notion. It facilitates every other step of the researching and writing process.

How much time do you spend reading per day?

It depends. When possible, I like to read first thing in the morning for an hour or so. Then throughout the day, I try to take any opportunity to read even just a page or two. If I’m frying an egg, for instance, I’ll read while the pan is heating up, while the egg is cooking, and while I’m eating breakfast.

Do you keep track of what cards you’ve used and haven’t used?

No. If I need to, I’ll search the various places online I might have used the contents of a notecard.

Do you make notecards for Ryan?

No. My job as his research assistant is to find material he might want to transfer into his notecard system.

How many notecards do you have?

I’m not sure. I have a box and ~1/4 full of cards. Each box holds ~1500 4×6 notecards.

What are you doing today that you wish you would have done from the start?

I review the cards way more than I originally thought was necessary. Almost daily, I engage with the boxes in one way or another.

How do you decide which cards you sift through before writing your Sunday newsletter?

The newsletter has evolved. In the beginning, I picked six random notecards and essentially transcribed them into the email service provider. So originally, I would go through all my notecards until I selected six. Recently, I’ve taken a more thematic approach to the newsletter. So I start with a vague sense of a theme—e.g. the ability to be in uncertainties and doubts without getting too stressed/anxious. Then, I have a pretty good sense of where I might find notecards that fit with that theme. So starting with a theme narrows my notecard search a bit, but because I’ve also found theme-relevant cards where I didn’t expect, I sometimes can’t help but expand my search beyond what is sometimes necessary.

V. Other People Who Use The Notecard System

“You’re better off starting imperfectly than being paralyzed by the hope or the delusion of perfection.” — Ryan Holiday

Ryan Holiday

Each one of Ryan’s books is comprised of thousands of notecards. What he does is he captures everything interesting he comes across. If there’s a good story in a book or a good line in a movie or a good lyric in a song, he writes it down on 4×6 index card and puts it in a box. When he goes through that box, he finds themes and makes connections that later become the idea for a book or a chapter or an article or a daily email or a talk or a video or a product or etc.

He first wrote about his system here and later, in this video, he explained his methods for reading, organizing what he reads, and using that information in his life and work.

I also recommend his article on the creative powers of the index card.

“It’s not an exaggeration: Nearly every dollar I’ve made in my adult life was earned first on the back or front (or both) of an index card. Everything I do, I do on index cards.” — Ryan Holiday

Ryan Holiday’s notecards

Ryan Holiday’s notecards

Robert Greene

Ryan adopted and adapted the notecard system from Robert Greene.

Robert talks about his system and shows one of his boxes of notecards here. And in his interview on the Knowledge Project podcast, starting around 12:50, Robert details how he reads, researches, marks up books, transfers material onto notecards, files those cards, and uses those cards to write his books.

When asked about why he doesn’t use a digital system, Robert said:

“Writing things out by hand has a logic to it. When I’m taking notes, when I’m scrawling with my fountain pen on a card—I’m thinking more deeply than when typing on a computer…The handwriting process links closer and faster to the way my brain works…Then, having a box of two thousand cards that I can sift through with my fingers and that I can move around with incredible speed—I can’t do that on a computer. It’s not the same process.”

Robert Greene’s notecards

Niklas Luhmann

The German sociologist Niklas Luhmann published some 50 books and 550 articles in various publications. When asked about his high quality and high volume output, Luhmann would credit his “slip-box” (or zettelkasten in German).

“Of course, I do not think of all this on my own; it mostly happens in my file…In essence, the filing system explains my productivity…Filing takes more of my time than writing the books…Without those cards, just by contemplating, these ideas would have never occurred to me. Of course, my mind is needed to note down the ideas, but they cannot be attributed to it alone.” — Niklas Luhmann

Niklas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten

Niklas Luhman’s notecards

Luhmann wrote a short essay about his slip-box as a communication partner here. And a Johannes F.K. Schmidt wrote a great paper, Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine.

The research analyst and developer Dr. Sönke Ahrens wrote a short book loosely based on Luhmann’s methods titled How To Take Smart Notes.

Tiago Forte

Tiago is the authority on digital note-taking, or—to borrow from the title of his popular online course and recent bestselling book—on Building A Second Brain (course, book).

Tiago’s methodology is app-agnostic. He’s a systems and principles kind of thinker, so even though I use physical notecards, his work has influenced the evolution of my processes.

Tiago also has a great piece on Luhmann’s slip-box system as written about in How To Take Smarts, which you can read here.

“What are the chances that the most creative, most innovative approaches will instantly be top of mind? … Now imagine if you were able to unshackle from the limits of the present moment, and draw on weeks, months, or even years of accumulated imagination.”

Tiago Forte’s Second Brain

Dustin Lance Black

In this video, the Oscar-winning filmmaker Dustin Lance Black (Milk, When We Rise) explains and shows how he researches, makes note cards, organizes those note cards, then lays out those note cards to write his screenplays.

“What I do is take that [research] material and boil down the moments that I think are cinematic, the moments that are necessary for this story, and I start to put them onto note cards. Each note card should be as pure and singular an idea as possible, because I want to be able to move all the pieces around and to create a film. And a film is not what happened. A film is an impression of what happened.” — Dustin Lance Black

Dustin Lance Black’s notecards

Dustin Lance Black’s notecard system

Vladimir Nabokov

After his death, Vladimir Nabokov’s final novel, The Original of Laura: A Novel in Fragments, was published. In it, you can see the notecards Nabokov made that he eventually would have pieced together into a cohesive novel.

Nabokov used this analogy for his notecard system—with each notecard, he was slowly assembling the structure of a book until he had what resembled, in his mind’s eye, the blocked grid of a crossword puzzle. Then, he went back and filled in the white space.

“The pattern of the thing precedes the thing. I fill in the gaps of the crossword at any spot I happen to choose. These bits I write on index cards until the novel is done. My schedule is flexible, but I am rather particular about my instruments: lined Bristol cards and well sharpened, not too hard, pencils capped with erasers.” — Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov notecard

Vladimir Nabokov’s notecard system

Erin Lee Carr

In this interview, Erin Lee Carr talks about how she turned to the notecard system when she was stuck during the process of writing All That You Leave Behind.

“From the beginning I found myself deeply challenged and stuck — freaked out by the blank page. So I started to use my skills as a filmmaker. I note-carded it. I had the notes above my computer, and I got to do a little “X” when I finished the draft of a chapter; it was this really satisfying moment.” — Erin Lee Carr

Erin Lee Carr’s notecards

Ronald Reagan

From the Reagan Foundation: “In the 1950s, Ronald Reagan began collecting motivational, entertaining and compelling quotes, writing them on notecards, from which he drew inspiration for his speeches.”

After Reagan won the 1980 presidential election, he and the speechwriter Ken Khachigan sat down to draft Reagan’s first inaugural address. Reagan took out his notecards. Khachigan said, “he had all this stuff he had stored up all these years — all these stories, all these anecdotes. He had the Reagan library in his own little file system.”

Ronald Reagan notecard

Ronald Reagan notecard

George Carlin

The comedian George Carlin said his system started when:

I had a boss in radio when I was 18 years old, and my boss told me to write down every idea I get even if I can’t use it at the time, and then file it away and have a system for filing it away—because a good idea is of no use to you unless you can find it…

“A lot of this,” Carlin said, “is discovery. A lot of things are lying around waiting to be discovered and that’s our job is to just notice them and bring them to life.”

George Carlin’s notecard system

George Carlin’s notecard

VI. Conclusion

“Many times the reading of a book has made the fortune of the reader,—has decided his way of life.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

There’s an argument I initially thought I might make here that would have gone something like this: if you don’t produce things with your notes, you’re wasting your time by taking notes. If you don’t currently create or have plans to create blog posts or books or songs or sneakers or etc., I thought I might argue, a note-taking process is a waste of time.

But then I thought more about it. I spent more time with my notecards. I paid closer attention when I was taking the pains to write things down. And now, I will make a different argument.

When you put stuff from a smart person’s brain into your brain, right then and there, you are changed. Your thoughts are downstream from your inputs. That’s something I’ve realized through the following bizarre and interesting experience. I’ll be talking or journaling and catch myself reciting (what feels like) word for word from a notecard I’d made. It’s bizarre because, as I said many times above, for the most part, I can’t remember the notecards I’ve made. It’s interesting because, wow, I’ll think, this experience couldn’t exist in this way if I hadn’t made that notecard.

When he was coming up as a writer, the author and journalist Rex Murphy would write out longhand favorite poems and passages. He was asked, what’s that done for you? “There’s an energy attached to poetry and great prose,” Murphy said. “And when you bring it into your mind, into your living sensibility, by some weird osmosis, it lifts your style or the attempts of your mind.” When you read great writing, when you write down a great line or paragraph, Murphy continues, “somehow or another, it contaminates you in a rich way. You get something from it—from this osmotic imitation—that will only take place if you lodge it in your consciousness.”

David Brooks talks about what he calls the “theory of maximum taste.” It’s similar to what Murphy is saying. “Exposure to genius has the power to expand your consciousness,” Brooks writes. “If you spend a lot of time with genius, your mind will end up bigger and broader than if you [don’t].”

The famous line from Emerson is, “I cannot remember the books I’ve read any more than the meals I have eaten; even so, they have made me.”

And same—I cannot remember the notecards I’ve made, but I like knowing they are both somewhere in my consciousness and somewhere in my box.

Want to see The Notecard System in action?

Every week, I pick six notecards from my collection to help me write my Sunday newsletter.

You can check out the archives here, and if you want to start receiving SIX at 6 in your email inbox every Sunday, drop you email in the thing below. Or email me and I’ll make sure you get added to the list.

No spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Thank you to Katie McKenzie, Alejandro Sobrino, Jeff Shannon, Joseph Lindley, Harry Lawrence, Kevin Rapp, Max Feld, and Stanley Goldberg for reading drafts of this.